What is rapamycin?

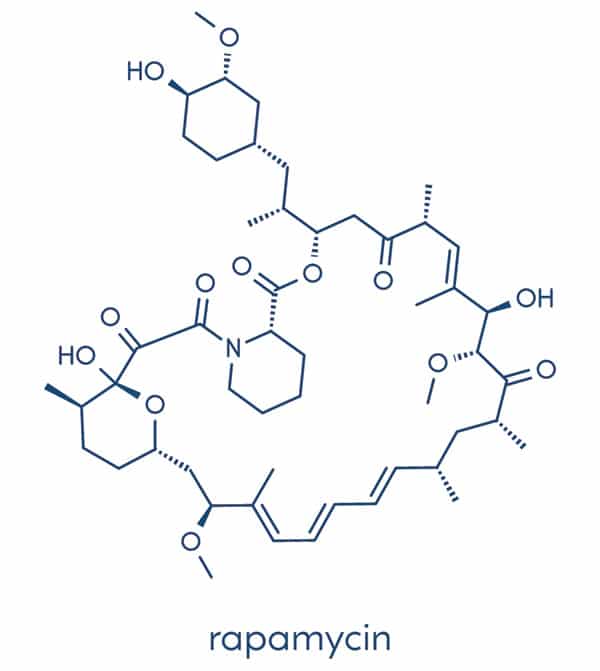

Rapamycin, also known as sirolimus, is an immunosuppressant drug that was approved by the FDA in 1999. Rapamycin demonstrates the greatest potential at slowing down the formation of senescent cells to slow aging and boost your performance at a cellular level.

Benefits of Rapamycin

The science behind Rapamycin Administration

Longevity pathways affected by Rapamycin:

- mTOR pathway

- Autophagy

- Insulin/IGF-1 signaling

- Senescence and inflammation

- Mitochondrial function

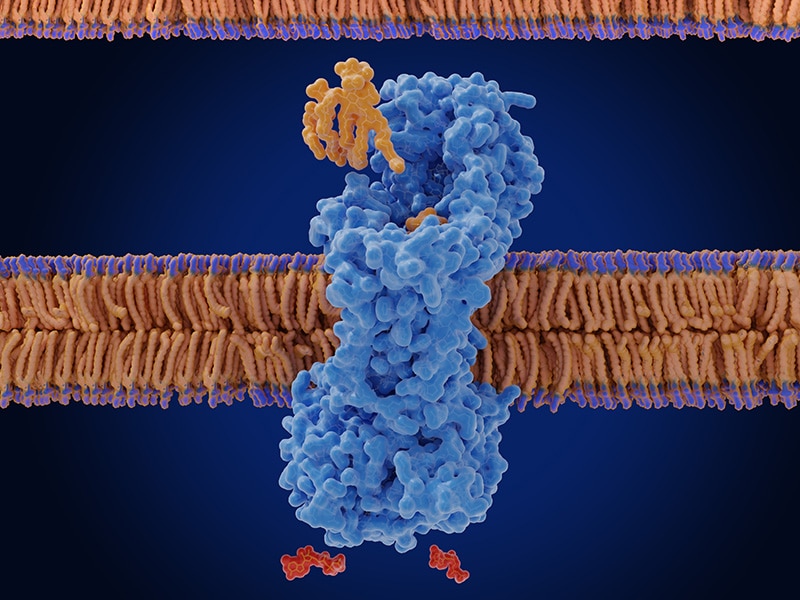

What is the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway?

The mTOR pathway, found in all cells, determines when a cell should grow and divide. However, with time, it can become too active, resulting in unchecked cell growth and compromised tissue health. This heightened activity speeds up aging and leads to issues such as cancer, cognitive decline, and metabolic challenges. Research reveals that managing mTOR activity can prolong the lifespan in various organisms, emphasizing its critical role in the aging process.

The mTOR pathway has been linked to multiple chronic disease processes such as:

- declining immune function

- deteriorating pulmonary function (leading to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease)

- diminishing bone mineral density (leading to osteoporosis)

- development of cancer

- atherosclerosis and cardiac hypertrophy in cardiovascular disease

- neurodegeneration.

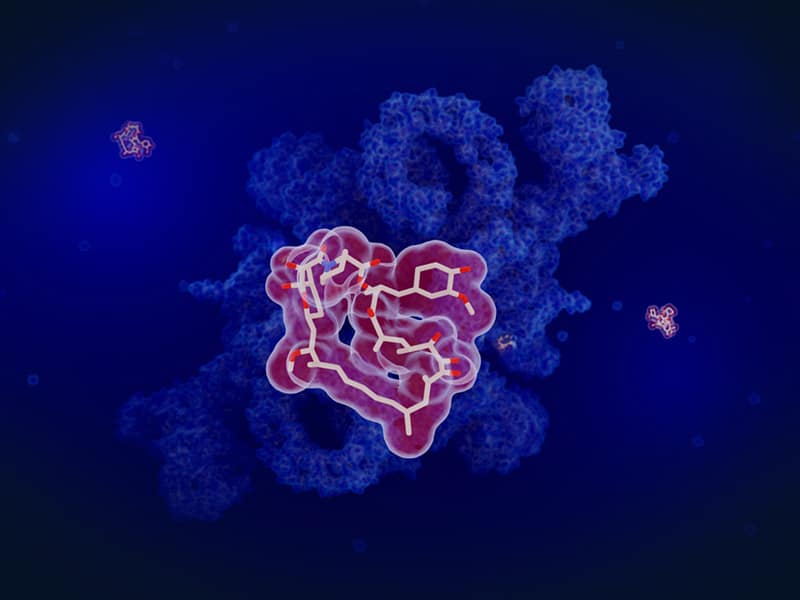

Rapamycin and its derivatives are inhibitors of mTOR. These drugs are approved for use in anticancer therapies, rejection prophylaxis after organ transplant, drug-eluting coronary stents, and the treatment of lymphangioleiomyomatosis and tuberous sclerosis.

Animal studies have shown that decreased mTOR signaling extends lifespan by up to 20% in yeast, 19% in worms, 24% in flies, and 60% in mice.

In humans, randomized controlled trials have shown that the administration of rapamycin derivatives alongside vaccines against seasonal influenza can boost immune response by reversing immunosenescence. We aimed to summarize the effects of rapamycin and its derivatives on the severity of aging-related physiological changes and disease in adults.

Rapamycin is a direct inhibitor of the mTOR pathway. Low doses of rapamycin appear to reset mTOR activity to a more youthful state—active when needed and dormant when not required.

Dosing

Mostly, 2 mg to 10 mg of rapamycin is taken, every week or every two weeks. Professor Michael Blagosklonny, an expert in rapamycin and longevity, even took a regimen of 20 mg of rapamycin every two weeks. Generally, the most often recommended rapamycin dose is between 2 and 8 mg once weekly or every two weeks.

Mostly, people take 5 to 7 mg weekly. Some experts recommend taking “rapamycin holidays”. For example, one takes rapamycin (bi)weekly for 3 months. And then takes a break of one month, during which one does not take any rapamycin, and then starts again a 3 month period. Other people take rapamycin for 3 months, and then take a 3-month break. As you can see, such dose regimens are considerably lower and different than when taken in an organ-transplant context, in which rapamycin is taken daily, sometimes 5 mg or more per day, and in combination with other very strong immunosuppressants. However, there have been longevity or health-focused studies in humans in which rapamycin is given continuously, demonstrating no serious side effects. In one study, a relatively low dose of 1 mg of rapamycin every day in elderly people (to improve immune function) didn’t lead to significant side effects and was shown to be safe.

In general, rapamycin has demonstrated to be a reasonably safe drug. Multiple clinical trials show that serious side effects are very low or non-existent. Some studies even show that side effects are higher in the placebo group than in the rapamycin treated group. In a failed suicide attempt one person took 103 tablets of 1 mg or rapamycin (so 103 mg in one go), with no significant side effects (only elevated cholesterol). However, when starting rapamycin treatment, it’s important to keep some things in mind, such as closely following specific blood biomarkers.